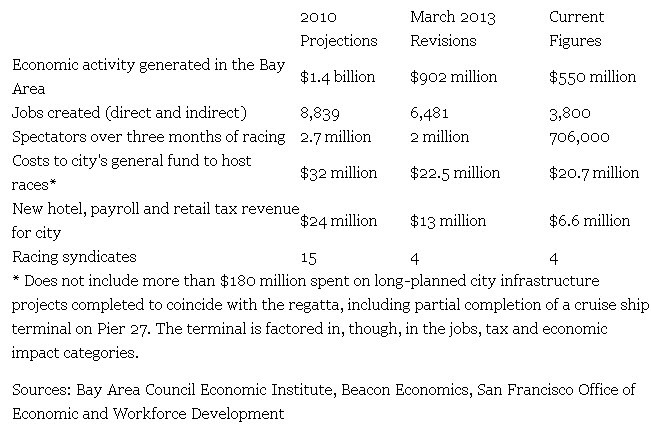

Nei giorni scorsi SF Chronicle ha effettuato un’analisi dettagliata su quale sia stato il reale impatto della Coppa America nella Baia di San Francisco. Partendo dai report del Bay Area Council Economic Institute emerge chiaramente quale sia stata la discrepanza tra quanto “trionfalmente” stimato nel 2010 e quanto realmente consuntivato nel settembre 2013. Si riporta integralmente il testo dell’articolo in maniera che ognuno possa fare le proprie considerazioni, ma ci preme enfatizzare che all’atto dell’avvio dei lavori l’ACEA (America’s Cup Event Authority) aveva previsto un impatto sull’economia della città di quasi 1,4 miliardi di dollari che nel marzo 2013 aveva rivisto a 900 milioni di dollari. In realtà l’evento ha portato nelle casse della città solo 550 milioni di dollari. A questo dato va aggiunto quello dei posti di lavoro creati: nel 2010 quasi 9000 per poi chiudersi a settembre con una stima di -62%. L’articolo enfatizza anche che, annunci trionfalistici a parte il 22 dicembre la città di San Francisco dovrà dichiarare se è realmente interessata ad ospitare un’altra edizione e quindi soltanto allora sapremo veramente quanto ne sarà valsa la pena ospitare un evento che è costato ai cittadini della Baia 5,5 milioni di nuove tasse per esaltare la vanità di pochi ricchi signori. Quindi aspettiamo la decisione di Ed Lee (sindaco di San Francisco nella foto con Stephen Barclay CEO ACEA) per capire veramente se ci sarà un’edizione bis nel 2017, soprattutto in considerazione che il grosso degli investimenti sarebbe già stato fatto per una città che già di per sé è una meta turistica.

America’s Cup: Financials from San Francisco fall short of projections

By John Coté, SF Chronicle

(December 10, 2013) – San Francisco is still in the red from hosting the 34th America’s Cup, which so far has cost taxpayers at least $5.5 million, according to draft financial figures from the regatta that The Chronicle reviewed Monday.

That spending, though, allowed the city to host an event that drew more than 700,000 people to the waterfront over roughly three months of sailing and generated at least $364 million in total economic impact, draft figures from the Bay Area Council Economic Institute reveal. That figure rises to more than $550 million if the long-planned construction of a new cruise ship terminal, which the regatta served as a catalyst to finally get built, is factored in.

Even the higher number, though, is well below the $902 million in economic benefit that was projected in March, a few months before the races were held. And it’s a far cry from the $1.4 billion economic boost that was originally predicted in 2010, when the races were billed as trailing only the Olympics and soccer’s World Cup in terms of economic impact.

Dec. 22 bid deadline

The real costs and benefits of hosting the regatta – the most prestigious competition in competitive sailing and this year the source of one of the most stunning comebacks in international sports – are expected to be in the spotlight as Mayor Ed Lee prepares to submit a preliminary proposal for hosting the next Cup by a Dec. 22 deadline.

Critics contend that using taxpayer funds for the event amounted to subsidizing a vanity race for the ultra-rich. Supporters view it as a smart investment that pumped up the local economy, brought international media coverage and prodded city officials to finish planned waterfront improvements that had languished, including better sidewalks and a promenade at Fisherman’s Wharf and a redone bike path and boat berths in the Marina District.

The Cup “showcased our beautiful city to the world and brought thousands of new jobs, long-overdue legacy waterfront improvements, international visitor spending, and a boost to our regional economy,” Lee said in a statement.

It came at a cost.

The city spent $20.7 million to hold the event, according to the latest figures from Lee’s office. That number does not include more than $180 million in long-planned improvements around the waterfront that were finally completed in advance of the event. The most notable was the new cruise ship terminal at Pier 27, which is only partially finished.

Ongoing private fundraising, which was intended to help cover the city’s event costs and initially pegged at $32 million, has so far only reimbursed $8.65 million to taxpayers, while also covering other obligations. If the net increase in city tax revenue of $6.6 million during the event is factored in, that still leaves taxpayers $5.5 million in the red.

“A $5.5 million deficit, all for a yacht race for billionaires,” said Supervisor John Avalos, who maintains that such money could have been better spent improving city services in outlying neighborhoods like the Excelsior, which he represents. “The whole event has been nothing more than a stupefying spectacle of how this city works for the top 1 percent on everyone else’s dime.”

‘Moving the goal posts’

Even applying event-generated tax revenue to the city’s bottom line was “moving the goal posts” from the original agreement in December 2010 with regatta organizers, Avalos said.

By early 2012, though, some city officials were already contemplating factoring in the tax revenue. A February 2012 report by board Budget and Legislative Analyst Harvey Rose projected city event costs at almost $52 million. With $32 million from the America’s Cup Organizing Committee and $22 million from event-related tax receipts, Rose’s report projected the city would have a $2.2 million surplus under that scenario.

That didn’t happen, but others say the event was still worth it.

“While the economic boost fell short of initial expectations, it’s definitely worth a modest city investment to generate hundreds of millions of dollars for our local economy,” said Board of Supervisors President David Chiu, whose district includes the northeast waterfront. “The race ended up being pretty exciting, too.”

Not including the construction of the new cruise ship terminal, the America’s Cup generated $364 million in economic activity at a minimum and created almost 2,900 jobs, according to the Bay Area Council Economic Institute.

By comparison, hosting the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, N.C., last year infused nearly $164 million into the economy, according to a report by consultant Tourism Economics. The New Orleans Business Alliance put the economic impact of hosting the last Super Bowl at about $430 million.

Economist’s view

But such rosy analyses are rife with problems, said Andrew Zimbalist, a renowned sports economist at Smith College in Massachusetts.

“The people who projected the benefits in the first place, they’re the ones who come out and say it was very good for the economy,” Zimbalist said.

San Francisco is already a popular destination in summer and September, and if “it’s just one group replacing the other, there’s no net impact at all,” Zimbalist said.

The latest numbers “sound very inflated and unrealistic to me, but I’d want to see the methodology,” he said. That was not immediately available. The final economic impact report is expected to be completed by the end of the month.

Surveys of attendees

Officials at the Bay Area Council Economic Institute said their figures were based on modeling after getting input from various sources, including more than 1,000 surveys of attendees, and were deliberately conservative. For example, no spending by San Francisco residents was included, with the argument that that money would have been spent locally anyway.

Event-related tax revenue for San Francisco was reduced from a high of $7.9 million to $6.6 million to account for hotel guests displaced from the city, said the institute’s vice president, Tracey Grose.

The race economics suffered from a lack of competitors after racing syndicates balked at the $100 million needed to field a competitive team during the global economic slump.

Interest was further sapped when the challenger matches, the Louis Vuitton Cup, featured a string of “races” with only one boat on the course. That occurred after the death of an Artemis Racing team sailor who was trapped underneath a capsized boat during training.

Oracle Team USA was also penalized in a cheating scandal but staged a stirring comeback from down 8 matches to 1. That drew thousands to the waterfront. On the final day of racing, the Embarcadero from the Ferry Building to Piers 27 and 29 was a sea of people, with spectators having to be turned away from the pier because it was at capacity.

“It obviously got off to a slow start,” said Sean Randolph, president of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute. “But things accelerated during the America’s Cup finals, and it ended with a substantial positive result.”